Royalty Free Music is a term that you’ll hear bandied around the place a lot, but not too many people really understand it’s meaning. Many people think because it has the word ‘free’ in it that the music must be free in monetary terms, free of copyright or even ‘license free’ in the sense you can share it with your friends and they can use it legally however they wish.

All those assumptions are wrong, but as you’ll often hear people talk about royalty free music as if it’s free, it’s often hard to know what ‘royalty free’ actually means. For that reason, we thought it a good idea to give you the low-down on its meaning and why it’s of benefit to you, the filmmaker, podcaster creator, vlogger or general media maker who wants music for your production without the licensing issue headaches.

What is a Royalty?

Let’s break things down and start with the term royalty. A royalty is a payment made to someone whether they are a musician, artist, writer or even movie producer per use of their work. Our friends at Google define it as:

A sum of money paid to a patentee for the use of a patent or to an author or composer for each copy of a book sold or for each public performance of a work.

Often, royalties are small amounts of money, however, it’s important to remember that unless you are someone who is obliged to pay royalties (like a broadcast TV channel), then you do not have to pay these royalties. In other words, the vast majority of people like yourself do not need to pay royalties! Wohoo! Crack open a free virtual beer on us (that one really is free).

So hang on, why should I be bothered about music being ‘royalty free’ then?

This is where confusion often arises as many people think that composers / artists / general groovy content creators are opting to not receive performance royalties by selling their work as ‘royalty free’.

Royalties come in many forms, but the royalty (or more accurately, the ‘sync’ fee) referred to in ‘royalty free’ is the fee that is normally required for repeated use of that music after a certain period of time has elapsed. Buying royalty free music means you pay once for use in your production forever i.e. it’s ‘free’ of the sync fee common in other licensing models.

Note that a composer is not giving away his / her royalties by selling royalty free music, but rather permitting you as a customer to bypass the common sync-fee model.

Take for example the common needle drop licensing agreement which requires you to renew your license every X days / months / years (this is the opposite of royalty free music which lets you use that music ‘in perpetuity’, which is posh talk for forever). The typical needle drop license model means content creators, like composers, agree specific terms for their music. Here’s an example of what a composer might agree under a needle drop license:

“You can use my track for 1 year on TV and radio in Europe and the USA for X dollars, after which, if you want to publish that work again, you must pay me to renew the license”

Needle drop licensing means a composer grants rights to someone / a company to use that track (often exclusively) for a set period of time. Performance royalties are then paid based on the number of times that track will be used, as well as the size of the territory within which it’s going to be broadcast, but you as the video producer pay nothing, the TV broadcast companies do.

What does all this mean for me?

Well, when you buy royalty free music as a filmmaker or vlogger for example, you will not be charged these types of ‘royalties’ as the music is ‘free’ of that type of royalty for you. You only pay the license fee to use that track in your production whether it’s an online advert, YouTube video, podcast or any other project like a film.

A royalty free license is usually a lot cheaper than a needle drop license, because you are not buying that track exclusively for a set amount of time and other people can buy and use those tracks at the same time as you. What you are buying is essentially use of that music in your project forever and non-exclusively if that makes sense.

There are minor exceptions to this that are specific to each library’s policy, for example, our cans and cannots of our music are here, but we think you’ll agree that ours is pretty flexible.

What is a cue sheet and how does it relate to royalties?

Content producers who wish to play music out in a public setting (whether broadcast or as background music in a pub) should fill in a cue sheet. If your production is going out on TV in a series, advert, film, radio programme or any other public broadcast setting, you should fill in a cue sheet with the programme and composer’s details.

Why? Partly because it’s required by most Performance Rights Organisations (PROs), but it’s also how a composer gets paid for their work being broadcast publicly and costs you nothing. As mentioned, this type of royalty is called a performance royalty and the broadcast company, like ABC or CBN will pay these, they just need a cue sheet to make sure those royalties reach the correct composer.

Why ‘royalty free’ then?

Well, quite. Many people in the music library industry have suggested alternative descriptions such as ‘Pre-Licensed Production Music’, ‘Single Fee Music Licensing’ and even ‘Pre-Paid Production Music’ as terms like this would help everyone understand what royalty free actually means.

Really, the term ‘royalty free’ should be laid to rest as it’s very misleading, but it seems it’s a phrase that’s going to be around for a while despite most people agreeing it’s stupid and misleading, like the Chuck Norris meme that makes him out to be invincible:

But really, it all amounts to the same thing and a little bit of education spread far and wide is all that’s needed.

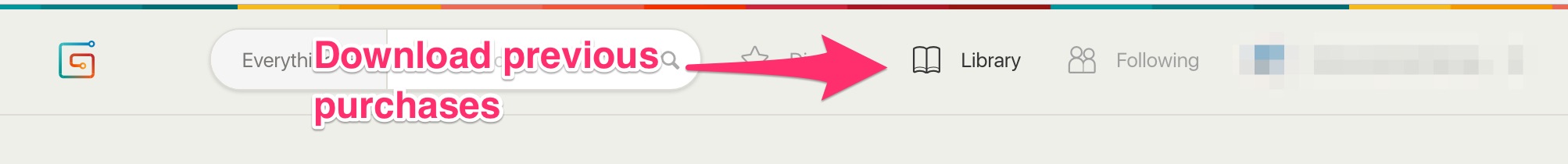

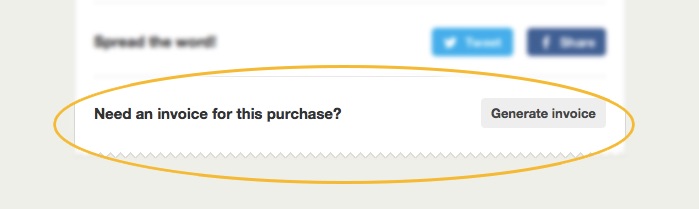

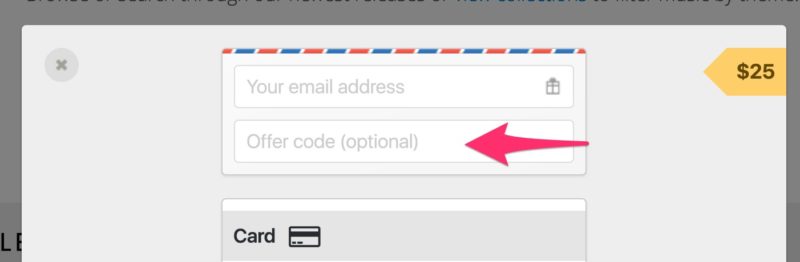

Downloads and invoices

Downloads and invoices